In

Memoriam

Dr Ivor Noël Hume,

OBE, FSA

By Sean Kingsley & Ellen Gerth

Ivor Noël Hume, Historical Archaeology (New York, 1969)

For almost seven decades Ivor Noël Hume – archaeologist, social historian, dramatist and novelist – bestrode excavated trenches as a colossus shining light on the unstudied post-medieval past. His life spanned extraordinary times that he embraced to become an extraordinary person of a substance and style rarely seen today.

Through his passion for the past Noël was revered by royalty and students alike, receiving honorary doctorates from the University of Pennsylvania (1976) and the College of William and Mary (1983). In 1991 he received the J.C. Harrington Medal, the highest award of the Society for Historical Archaeology in America, which he co-founded in 1967. Queen Elizabeth II appointed Noël an Officer of the British Empire in 1992 in recognition of his services to British culture.

|

|

Ivor Noël Hume excavating a bomb-damaged site in the City of London for the Guildhall Museum (1949/early 1950) Photo: thamesdiscovery.org |

Noël coined the phrase the “handmaiden of history” to describe the role of post-medieval excavation on the discipline, and students and scholars affectionately call him the ‘godfather’ and ‘grandmentor’ of historical archaeology. Academics referred to Noël as a “larger-than-life figure – part Sir Lancelot, part Babe Ruth, part Howard Carter”. His pioneering Guide to Artifacts of Colonial America is considered a bible for understanding the post-medieval artefacts of America and Britain – from types of 17th- to 18th-century glass bottles to wig curlers and iron padlocks – while students unanimously judge Martin’s Hundred (New York, 1982) to be the best book written in the field.

Ivor Noël Hume never intended becoming a player in the nascent field of archaeology. Theatre was his first love. After leaving the army in 1945 he took a position in London as an assistant stage manager for the J. Arthur Rank organization, hoping to advance from writing childhood plays to becoming a bone fide playwright. While knocking on the doors of theatrical agents for four years, Noël happened to hear a BBC radio show about a man finding antiquities along the River Thames. With time on his hands, Noël decided to take a look for himself.

Impressed by his handling of these relics, the archaeologist

|

|

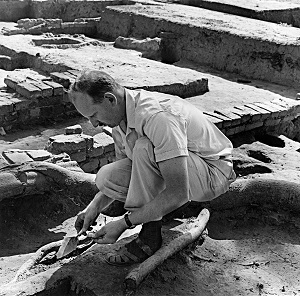

Ivor Noël Hume

digging at Carter's

Grove, Colonial

Williamsburg. Photo © The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation |

(see Blair and Watson, ‘The Great Fire of London: Ivor Noël Hume’s Investigation of the 17th-Century Material

Culture of the Metropolis’, in E. Klingelhofer (ed.), A Glorious Empire, Archaeology and the Tudor-Stuart Atlantic World. Essays in Honor of Ivor Noël Hume (Oxford, 2013), 106-18).

|

|

Ivor Noël Hume

producing the late

1970s film

Search for a Century.

|

At Williamsburg, dug since 1928, the playwright turned past-hunter found fertile new ground for exploration. At the time the excavations were essentially clearance operations exposing the architectural plans of buildings. Colonial Williamsburg’s staff knew little of archaeology and most artefacts uncovered were simply thrown back into the trenches. Nevertheless, Noël focused his attention on those unwashed finds that had been saved and stored in old fish boxes.

As in London, Noël’s skill set was quickly appreciated. In 1957 he jumped continents with his first wife, Audrey, to begin a career in the United States that would span more than five decades. Noël rose from the position of Chief Archaeologist at the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation to Director of Archaeology in 1964 and Foundation Archaeologist in 1983. During his Williamsburg tenure he directed many excavations at the Public Hospital site (1972-73, 1980-81), the James Anderson House (1984-75), the Chiswell site (1970), Prentis Store (1969), Wetherburn’s Tavern (1965-66), the Custis House site (1964), Captain Orr’s Dwelling (1963), the Travis House site (1962), the Anthony Hay cabinet shop (1960-61) and the Coke-Garrett House (1959).

Noël’s publication record was prodigious and unprecedented in the archaeology of post-medieval America. His two-volume final report with Audrey Noël Hume on The Archaeology of Martin’s Hundred (University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, 2001), an early 17th-century settlement at Carter’s Grove largely destroyed in the 1622 Algonquin Indian uprising, set the stage for profound physical and historical insights into the first decades of English settlement in America.

|

|

Former President

Richard Nixon and

his wife, Pat,

examining artefacts

with Ivor Noël

Hume in the Colonial

Williamsburg

Archaeology

Laboratory.

Photo: © The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. |

Making the past accessible to the public was key to Noël. The exhibitions he helped set up started with ‘Recent Discoveries in London’ at the Guildhall Museum in 1950 and included a 1960s exhibit on archaeology for the Colonial Williamsburg Visitor Center, an exhibit on the relationship of archaeological finds to history at the Anderson House in Williamsburg (1970), and the design and creation of the Martin’s Hundred exhibit in the Winthrop Rockefeller Archaeological Museum.

Noël also wrote and directed for Colonial Williamsburg the film Doorway to the Past, which won the Cine Golden Eagle at Washington in 1970 and the Chris Statuette (top award in Social Studies category) at the 18th Columbus Film Festival in 1970. Noël again wrote and narrated Search for a Century, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation’s film on archaeology at Carter’s Grove, which in 1981 won the gold medal at the Twenty-Fourth Annual Film and TV Festival in New York.

Noël’s past was an inclusive, generous and non-elitist realm that extended to marine archaeology. In shipwrecks he observed “archaeological data unparalleled on any terrestrial site. They are, in effect, time capsules unintentionally torn from the pages of history. Unlike the trash that the archaeologist must make the most from on land, wrecked ships contain cargoes of complete objects, all irrefutably associated and possessing an unimpeachable terminus ante quem” (Historical Archaeology, New York, 1969: 189). By the time Noël joined the UK Maritime Heritage Foundation’s Scientific Advisory Committee in 2012, he had published Shipwreck! History from the Bermuda Reefs in 1995 and Wreck and Redemption: William Strachey’s Saga of the Sea Venture in 2009.

|

|

Ivor Noël Hume

inspecting with

Ellen Gerth the

Remotely-Operated

Vehicle Zeus, a tool

of deep-sea

shipwreck

archaeology.

Photo:

© Odyssey Marine

Exploration.

|

Noël brought his great experience in helping turn archaeology into a professional field in America and solving heritage crises to the Maritime Heritage Foundation’s drive to see the first-rate British warship the Victory, lost in the western English Channel in October 1744, scientifically excavated. The intent, still ongoing, was for the finds to be turned from an inaccessible loss to publicly accessible in an English museum.

By 2012 Noël had six decades of experience in conflict resolution, including in the 1950s and 1960s helping resolve acute problems of identity and legitimacy in American archaeology. Despite these skills he told colleagues of his bewilderment about what he called a highly political ‘witch hunt’ to interfere in the archaeological recovery of the Victory by some UK heritage managers. Noël expressed concern about why some in the cultural heritage community pursued a policy favouring leaving shipwrecks to rot or be destroyed by trawl nets and illicit salvors, rather than excavated, an approach that was nonsensical to Noël’s pragmatism and extensive real-world experience. As early as 1963 he shared his inclusive approach to archaeology in Here Lies Virginia. An Archaeologist’s View of Colonial Life and History (University Press of Virginia), where he found it strange that:

"A profession dedicated to studying and separating one time frame from another has such difficulty recognizing and being charitable toward the phases of its own evolution. What was good archaeology in the last century can be unacceptable today, but to condemn its practitioners for not being as smart as we think we are is not only misleading, it implies that we lack the single attribute that all good archaeologists must possess: the knowledge and wisdom to put ourselves in other fellow’s historical place."

Noël’s analysis of UNESCO’s approach to underwater cultural heritage concluded that it was rooted in misguided regulations. Although he accepted that the Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage was created with the best of intentions, Noël was worried by its misuse to provide, as he put it:

"Wording that uninformed government bureaucrats could use to deny licenses for legitimate archaeological work. UNESCO’s choice of in situ preservation as its first goal, essentially means “don’t do anything that might disturb the remains.” But we all know that the purpose of archaeology, whether it be on land or underwater, is about disturbing the remains. We have to dig it to see it… In short, a code of ethics can encompass whatever we want to put between its covers. If its writers are seniors in their sphere, we assume that they are right and slavishly subscribe to their views. We know that even if we find flaws in their reasoning, it can be career damaging to say so. Thus fear transcends reason. The well-intended UNESCO 2001 Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage is just such a code. In its efforts to become all embracing in its protection of the sunken past, it puts much of it out of reach of the very people it was supposed to please and educate… it is remarkable that some people in the cultural resource community interpret UNESCO’s ‘first option’ for in situ preservation as a preference or even a requirement that any wreck remains in situ, i.e. unexcavated. Had that policy been established before the Mary Rose was raised, one wonders how much public interest would have been engendered by knowing that the wreck still lies in the Solent silt? By almost every one of UNESCO’s ‘Rules’, the Mary Rose project would today be in violation, as would most ground-breaking underwater recoveries of the past."

Ivor Noël Hume came to archaeology through one stage door and exited through another. At the end of his final presentation to the Society of Historical Archaeology, with a “Thank you and goodbye”, and against a backdrop of fervent applause and stunned surprise, he walked alone down the centre aisle and slipped out the door.

In later years Noël continued to think deeply and write profusely, finishing the play, The Life and Death of Cap’n John, and publishing his masterful A Passion for the Past. The Odyssey of a Transatlantic Archaeologist (University of Virginia Press, 2010) and Belzoni: The Giant Archaeologists Love to Loathe (University of Virginia Press, 2011) about the Italian circus explorer to Egypt. In his final months he was still hard at it, sending manuscripts to Ceramics In America and seeking a publisher for yet another completed novel. His shining light will be sorely missed.

Dr Ivor Noël Hume, OBE

Born London 4 November 1927, died Williamsburg 4 February 2017

Noël leaves behind his wife, Carol, and four stepchildren, Andrea, David, Michael and Kristen.

Select Writing

1950: Discoveries on Walbrook 1949-50 (Guildhall Museum Publication, London).

1953: Archaeology in Britain (Foyle, London).

1956: Treasure In The Thames (Frederick Muller, London).

1956: ‘A Century of London Glass Bottles, 1580-1680’, The Connoisseur Year Book, London, 98-103.

1957: ‘Wine Relics from Virginia – Jamestown and the First Colonists’, Wine & Spirit Trade Record, journal of the London wine trade, February 18, 1957, 154-60.

1961: ‘The Glass Wine Bottle in Colonial Virginia’, Journal of Glass Studies, Vol. III, Corning, New York, 91-117.

1964: ‘Romano-British Potteries on the Upchurch Marshes’, Archaeologia Cantiana, Vol. LXVIII, 72-90.

1964: ‘Archaeology: Handmaiden to History’, The North Carolina Historical Review, Vol. XLI, No. 2, 214-25.

1967: ‘Rhenish Gray Stoneware in Colonial America’, Antiques, Vol. XCII, No. 3, September 1967, 349-53.

1968: ‘A Collection of Glass from Port Royal, Jamaica’, Historical Archaeology, Vol. II, 5-34.

1969: The Wells of Williamsburg: Colonial Time Capsules (Colonial Williamsburg Archaeological Series No. 4).

1969: Historical Archaeology (Alfred A. Knopf, New York).

1970: ‘Archaeology: Doorway to the American Past’, The Athenaeum Annals (Athenaeum of Philadelphia), Vol. XVI, No. 2, 3-22.

1970: A Guide to Artifacts of Colonial America (Alfred A. Knopf, New York).

1973: ‘Historical Archaeology: Who Needs it?’, Historical Archaeology, Vol. VII, 3-10.

1974: All the Best Rubbish (Harper and Row, New York).

1982: Martin’s Hundred (Alfred A. Knopf, New York).

1983: ‘Pragmatism and Professionalism: A Cellarman’s View of the Ivory Tower’. In A. Ward (ed.), Forgotten Places and Things. Archaeological Perspectives on American History (Albuquerque), 1-9.

1994: The Virginia Adventure. Roanoke to James Towne, An Archaeological and Historical Odyssey (Alfred A. Knopf, New York).

1996: In Search of This & That. Tales from an Archaeologist’s Quest (The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Virginia).

2001: If These Pots Could Talk (Chipstone Foundation, University of New England Press).

2001: The Archaeology of Martin’s Hundred, Volumes I-II (Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology) (with Audrey Noël Hume).

2005: Something from the Cellar, More of This and That (the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Virginia).

2010: A Passion for the Past. The Odyssey of a Transatlantic Archaeologist (University of Virginia Press).

2011: Belzoni. The Giant that Archaeologists Love to Hate (University of Virginia Press).

2014: ‘X Commandments’, Ceramics in America (Chipstone Foundation).

2016: ‘A New Bloome’, Ceramics in America (Chipstone Foundation).